Orange Springs History

Orange Springs has been valued by humans for centuries. Indigenous peoples likely visited the spring long before European settlers arrived. During the Second Seminole War (1835–1842), a fort named Fort Russell was built nearby as part of the conflict and the U.S. government encouraged settlement through the Armed Occupation Act of 1842. In 1843 John W. Pearson and Senator David Levy Yulee purchased the spring property and turned it into a thriving health resort. By the early 1850s the resort included a large hotel, mills, shops and a church and welcomed visitors who travelled by steamboat and stagecoach to "take the waters".

The Civil War disrupted Orange Springs. Pearson organized the Oklawaha Rangers militia and produced arms for the Confederacy. After his death in 1864 and a tax sale in 1875, the resort declined. In the late 19th century the property changed hands several times. In 1912 turpentine entrepreneur James W. Townsend built the two‑story frame house that still stands today. The "Townsend House" served as a seasonal home and base for Townsend's business but also became a local landmark. Townsend died in 1944 and the house fell into disuse until the 1970s, when his granddaughter restored it and briefly reopened it as a bed‑and‑breakfast inn. It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1988.

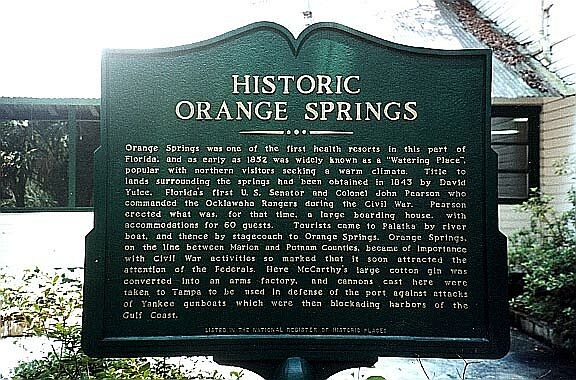

Although attempts to revive Orange Springs as a tourist destination continued into the early 20th century—promoters even marketed it as a "Fountain of Youth"—they never regained its antebellum popularity. Public swimming at the spring ended around 1990 when a bottled water plant opened on the site. Today, Orange Springs remains quiet but retains its historic structures and rich heritage. The Townsend House is preserved as a private office and historic site, and a state marker commemorates the spring's storied past.

James W. Townsend House: History, Legends & Legacy

The James W. Townsend House – sometimes called the Orange Springs Inn – is a two‑story vernacular home that has come to symbolize Orange Springs itself. James W. Townsend, a turpentine magnate who built an empire from Florida's pines, constructed the house in 1912 as a family retreat and base for his business operations. The structure reflects a mix of vernacular traditions: it began as a classic dogtrot house with an open central breezeway flanked by rooms on either side but soon evolved into a two‑story I‑house with a wraparound porch, chamfered posts and simple scroll‑sawn brackets. Built from locally milled lumber and resting on brick piers, the white‑painted house was designed to offer comfort in Florida's heat. Even today, its green‑trimmed veranda and airy porches remain a striking sight under the moss‑draped oaks.

Long before Townsend's era, Orange Springs was known for its mineral spring and health resort. In the 1840s and 1850s entrepreneur John W. Pearson built a resort here with hotels, mills, a store, a cotton gin and more. Visitors travelled from afar to "take the waters," believing the sulfur‑rich spring could heal ailments. The Civil War turned Orange Springs into a refuge; Pearson's machine shop produced muskets and even a cannon for Confederate forces. By the war's end and Pearson's death, however, the resort declined and was sold in 1875. When Townsend purchased the property around the turn of the century, he found a landscape dotted with abandoned buildings and vast pine forests ripe for turpentine. His new house would become the grandest residence in the quiet hamlet.

Townsend's turpentine empire stretched across several counties, and he used the Orange Springs house as a seasonal headquarters. Family stories describe cattlemen and turpentine workers visiting, while children played by the spring. The house retained its prominence even as Orange Springs slipped into obscurity. In the 1970s Townsend's granddaughter restored the home and opened it as a small inn; guests were treated to tales of healing waters, Confederate cannonry and ghostly legends. In 1988 the house was listed on the National Register of Historic Places for its architectural significance and association with Townsend. Although it is now a private office, the house stands as the largest historic residence in Orange Springs and a bridge between the town's frontier past and present.

Building the Townsend House (1912)

In 1912, at the age of 48, James Townsend undertook the construction of a substantial residence at Orange Springs – the very house that stands today bearing his name. By this time Townsend was a wealthy and prominent figure, and the new house would serve as his personal retreat and operational base in the heart of his Marion County timber lands. Family accounts describe the home as a "vacation house" where he could oversee his business interests "in relative comfort," and its location spared him the long journey back to Lake Butler while managing turpentine camps and groves in Marion and Putnam counties.

Architecturally the Townsend House is both practical and nostalgic. Although built in the 1910s, its wood‑frame vernacular design harkens back to frontier styles often described as classic Florida "cracker" architecture. In form it most closely resembles a two‑story dogtrot house – originally the centre breezeway was open to promote ventilation and flanked by rooms on either side. This breezeway was enclosed soon after construction, effectively turning the home into a Southern I‑house (two stories, one room deep, with a central passage) while still retaining breezeway spaces on both levels. The structure sits on brick piers, is capped with a simple metal roof and boasts a broad two‑story wraparound veranda adorned with chamfered posts and modest scroll‑sawn brackets. Built entirely of locally milled lumber, it offered ample shaded outdoor space and protection from Florida's heat.

The interior originally contained two large bedrooms on each floor separated by the central hall, reflecting the dogtrot lineage. Evidence suggests that the enclosure of the breezeway happened early in the house's history, since interior wall finishes show no obvious breaks where openings once were. Local lore adds that Townsend spared no expense: timber came from his own lands and was milled nearby, ensuring every beam and plank was sturdy Florida pine. A small spring bubbled just a few hundred yards away, and it's said that Townsend piped the mineral water to the house for drinking and bathing – a continuation of the "healthful waters" tradition that made Orange Springs famous. Whether or not that tale is true, the home quickly became the grandest dwelling in the hamlet – "the largest historic residential structure in Orange Springs, a community with a population of less than 100" – standing out with its green‑trimmed porches beneath moss‑draped oaks.

The Townsend family used the house as a seasonal residence and headquarters. James and his wife Lora raised their ten children primarily in Lake Butler, but they spent significant time at Orange Springs, especially during the winter. Family anecdotes recount cowboys and turpentine camp workers dropping by to confer with "Mr. Townsend," locals trading news on the porch and children fishing in the spring run. The broader community remained a company town centred on Townsend's enterprises; the old antebellum hotel and spa buildings were used for storage or worker housing. The mineral spring itself still flowed clear and was free for locals to enjoy, but no large tourist development returned during Townsend's life.

Twentieth‑Century Changes: Decline, Preservation & the Orange Springs Inn

After Townsend's death in 1944 the house entered a period of decline. The naval stores boom waned mid‑century and many turpentine camps closed. Lora Townsend lived in Lake Butler until 1958 and the Orange Springs property passed to descendants. For a time the big house sat largely unused except for occasional family visits. Orange Springs itself verged on becoming a ghost town – by the 1960s only a handful of families lived nearby and many original buildings had vanished. One account from 1962 described Orange Springs as "a ghost city" with only a few structures remaining. The Townsend House was one of those survivors: shuttered, paint peeling, but structurally sound.

The story took a positive turn in the 1970s when Townsend's granddaughter Martha Townsend Turner decided to revive the family legacy. She and her family installed modern bathrooms and a kitchen (enclosing portions of the porch for indoor plumbing) and refreshed the interior while preserving its historic character. Seeing potential in heritage tourism, they opened the home to paying guests. By 1986 the James W. Townsend House had been officially converted into a country inn and restaurant called the Orange Springs Inn. The first floor served as a dining area and lounge, complete with a commercial kitchen and public restrooms, while upstairs bedrooms were refurbished for guests. Visitors could relax on the upstairs veranda and listen to stories about antebellum spa visitors, Confederate cannonry and ghostly legends. In 1988 the house was listed on the National Register of Historic Places, recognising its architectural and historical importance. Although the inn later closed and the property is now used privately for events and offices, the Townsend House remains a cultural landmark that links Orange Springs' past and present. Its green‑and‑white exterior and sweeping porches continue to evoke images of James Townsend relaxing in a porch chair or guests arriving to sample the famous spring. A state marker identifies the site, and local historical societies occasionally organise tours. Thanks to preservation efforts, the house – once nearly forgotten – stands as a cherished piece of Florida frontier history.